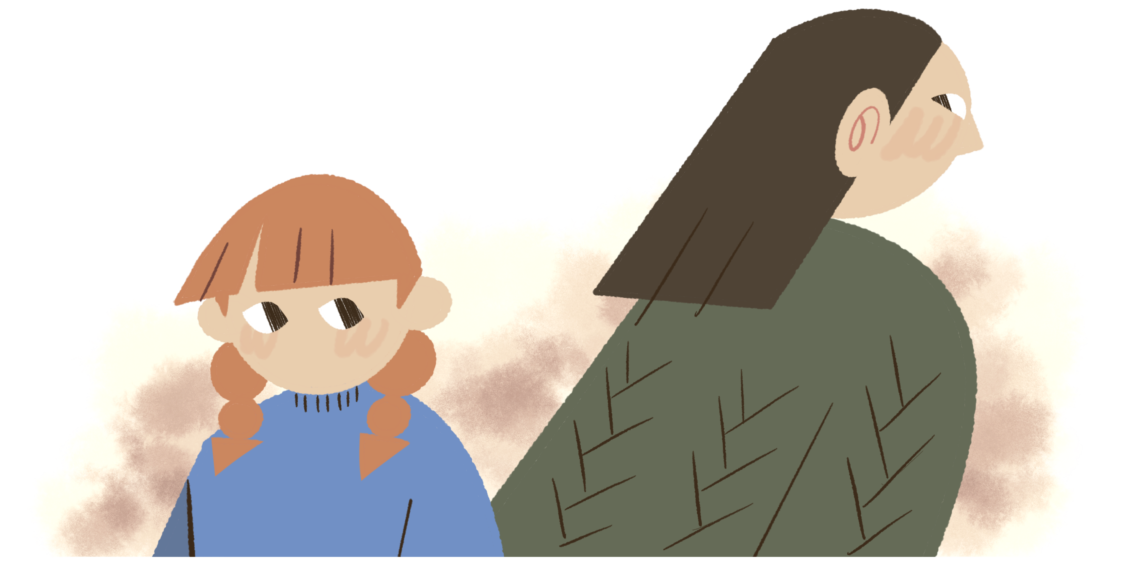

Not the Gilmore Girls

Until the age of six, my mother was my best friend.

I wanted to spend all my time with her. I would cry when she went to work, trying to hide her apron and tip pouch so she wouldn’t be able to leave. Even as a baby I was always trying to find my way back to my mother, using my father and grandmother as human leap pads to land myself back into her arms.

I remember us spending hours playing with my toys, crafting mythical worlds full of Barbies and Beanie Babies with storylines that could rival soap operas. She would let me run the show, taking the role of dutiful actress and never going off script—except for the occasional perfectly landed improvised line.

We would have afternoon picnics, usually with take-out fish and chips on an old floral patterned sheet. There was no wicker-woven basket, checkered blanket or crustless cucumber sandwiches, but she would let me feed my halibut to stray cats and toss my french fries to seagulls, so I thought it was perfect.

When her and my father fought, I took her side, even though she instigated every single argument. I told her she was right, even though it was her who threw the ketchup bottle that shattered against the wall. And it was her who kicked the hole in the bathroom door and the hall closet. And it was her who twisted my arm and taught me it’s better to say sorry than to stand up for myself.

Somehow, despite all this, she could do no wrong in my eyes. She was my mom and best friend, I wanted to see the best in her.

When my father finally left, I believed it would fix everything. I tried to convince myself that my parents weren’t happy, that my father brought out a monster buried deep inside my mother and that his absence would send it back to hibernation.

But even after he left, the monster was still hungry for flesh. Her claws still needed something to dig into and I was chosen to be her new emotional scratching post.

At first I thought if I did everything perfectly, she wouldn’t have a reason to be angry. I would get straight A’s on my report cards that were never taken out of the envelopes. I would try to wash plates that were too heavy with gloves that were too big, perched on a wobbly stool so I could reach the sink.

She couldn’t get angry at me if I did everything perfectly, right?

But there were still holes being kicked in the doors. She would tell me I was lazy, that I was ungrateful, that I ruined her life. I wouldn’t say anything, remembering the times she twisted my arm. I didn’t want to do anything that would stoke the anger raging inside her, so I remained silent.

I began to realize that there was no master plan I could conjure up to make her happy. There weren’t any rules or strategies I could deploy with my mother—just consequences buried like landmines.

I blamed myself, internalizing guilt and shame for my inability to make my mother love me. I convinced myself that it was my fault that we didn’t have the mother-daughter relationship that the media had force-fed me my whole life. That I had somehow derailed our relationship from being one like Lorelai and Rory’s on Gilmore Girls. I offered apologies in absence of the ones she owed me, begging her to forgive me for breaking my heart over and over again.

The final blow came when she “lost” the storage unit containing most of my childhood memorabilia last summer. The treasures I had saved for most of my life; the crafts I made in art class, the jewellery box containing necklaces with BBF engravings, my high school yearbooks with messages from people no longer here—all gone.

She claimed to have missed some payments but I knew better. She had finally shown me how little I meant to her, that some quick cash was worth more than my childhood.

I finally realized that the blame didn’t lie with me. There was nothing that I did wrong, there was no amount of A’s I could’ve gotten or dishes I could’ve washed that would’ve changed things.

I know now that I didn’t deserve the abuse. That I didn’t deserve the nights I spent eating old Halloween candy because I was scared to come out of my room. That I didn’t deserve the times she kicked me out and the rough hands I let touch me just so I would have somewhere to go. That I didn’t deserve to believe in a conception of love that runs so parallel to abuse.

I know now that I don’t have to persuade people of my worth. I deserve love and my mother’s refusal to do so is her loss, not mine.

It’s not always easy and it’s a relationship I will mourn for a long time. I haven’t forgotten her birthday even if we haven’t celebrated it together in two years. I still avoid Instagram on Mother’s Day and try not to feel empty for having nothing to post.

Nostalgia will still pull on my heart every so often as I remember the picnics or fantastical productions we would put on, but I’ve learned that I can love the version of my mother that exists in my memories without ever wanting to see her again. Some loves are meant to be distanced—even if that distance is counted in years instead of miles. We can’t return to the past, but it also cannot be unwritten and there is comfort in that. My mother may have disintegrated our relationship but she can’t take away those memories, they get to remain safe.

When I tell people I’m not in contact with my mother, they often tell me “forgiveness is the most important thing” and “you can’t choose your family.” These are two dirty lies that are weaponized to pressure people back into abusive homes just because they share blood. The family I’ve chosen for myself, the one comprised of me, my partner and our cat, has made me feel more at home in the last year than I ever did during the 24 I spent with my mother.

And also, I have chosen forgiveness. I’ve just chosen to give it to someone who deserves it: myself.

About the author

Olivia Matheson-Mowers is a former reporter for Youth Mind. When she’s not writing, or playing with her cat, Daisy, you can find her curled up in her heated blanket watching seasons 1-6 of Dragon Ball Z and complaining about seasons 7-9.

One Comment

Rachel

In my opinion…when someone tells you to “choose forgiveness”…well, that’s a form of gaslighting. It’s a way of minimizing the abuse committed against you, and frankly, you don’t have to forgive your abusers. Especially if they don’t want to get help for themselves. It’s ok to be angry, sad, confused, and to distance yourself from the trauma. Often people get told in response to struggling with intrusive memories and flashbacks, “you just can’t let go at all!” In reality, with trauma, nothing ever gets “let go”…but rather that you learn how to cope with it.